Ancient egypt Privileged location

|

| Ancient egypt |

Over the next 3000

years, Egypt prospered despite hardships, internal conflicts and foreign invasion. Herodotus, the Greek historian who traveled to Egypt in the

5th century BC, called it “the

gift of the Nile.”

Wind and water

The Nile is the source of all Egyptian life. Without that sacred

river, all this land would have been barren, dried by the broiling sun

and the wind. Rainfall gradually diminished in the area

of Egypt, start- ing around the beginning of the third millennium BC;

over time, it be-

came almost non-existent.

People began

concentrating along the nar- row

strip of land on both sides of the river, where they survived by fish-

ing, hunting,

gathering, farming and breeding livestock. The

remaining

region was desert, known as deshret (“red land”) — an area that was regarded as sinister and perilous, and was often avoided. The black soil

and the narrow colonized strip of land alongside the Nile was called khemet (“black land”); it provided a sharp contrast to the lifeless “red

land.”

The Nile received its modern name from

the Greeks, who referred to the river as “Neilos.” The Nile is the longest river in the world —

almost 4200 miles long — yet it is only 500

yards wide. Out of Ethiopia

rises the Blue Nile and from Uganda comes the White Nile. They con-

verge at Khartoum, Sudan, flowing northward into Egypt, becoming

Iteru Aa (or “the Great River,” as it was known to the ancient Egyp- tians).

The Nile is the only

major river to

flow north; its many

tributar-

ies originate in the mountains south of the

equator, and it cuts through hills, deserts and riparian marshes to empty into the

Mediterranean Sea

or

Wadj Wer (“the Great Green”). (Both “aa” and “wer” translate into

“great.”) Thus, Upper Egypt and Deshret are located in the southern region while Lower Egypt, the marsh area and the Delta are situated

to the north. Both regions were known as taui (“the two lands”). The northernmost area, where the waters fan

out into streams in a triangu-

lar-shaped region, is known as the Delta, the name of the fourth letter of

the Greek

alphabet

whose shape it resembles.

Each summer, rains from Africa cause the waters of the Nile to rise

and temporarily flood the land, depositing a new layer of rich silt

ideal for growing crops. The fertile valley and warm climate afforded an

optimal environment for the villagers or fellahin to

become proficient

in the science of agriculture.

Ancient Egyptian civilization was based upon the fertility of the soil; seeds were planted

that only the Nile could

nourish. The annual flooding also left behind immense thickets of

papyrus. This versatile reed was converted into myriad

necessities in- cluding paper, rope, fabric, sandals, baskets, mats, stools and river rafts.

Every year, the settlers watched and waited with anticipation

hoping that the waters would

rise high enough

to ensure irrigation. As the settlements grew,

not only in number but in size,

the

collective ef- fort, the commitment to

cultivating the land, required the organization

of

extensive labor; the expanding irrigation works were an enterprise that

had to be performed on a grand scale and this, in turn, became cru-

cial in the development of the community.

Measuring and recording the level of the annual flood was a mat-

ter of national importance; the device used for this task was called a “Nilometer”. It consisted of simple markings, in the form of a descend- ing staircase leading down into the river; the depth of the rising waters

was observed

and documented by officials who used

this economic predictor to

set

the level of taxes based on the prospective crops for the

coming year. The ideal height for the waters to

rise, based on the Nilometer, was

about 25 to 30

feet. Low water — anything

less

than six feet below the target — meant food shortages, and possibly famine.

Highs of six feet over

the ideal meant disaster as well — the destruc- tion of protective dykes, dams, and mud-brick homes, and the flooding of

entire

villages.

In

successful

years, the Nile overflowed during

the summer

months and flooded the valley, setting the scene for the year ahead. The

agricultural cycle consisted of three seasons, based upon the cycle

of the Nile. The first and most important was called Akhet,

the season of inundation that took place from mid-July to

mid-November. Akhet was followed by Peret, or Proyet, the season of emergence or “coming forth,”

when

growth occurred, from mid-November to mid-March.

During this time, the farmers worked the fields, and reaped their grain and

flax. The third season, when the river was at its lowest, marking the end of the

harvest, spanned from mid-March to mid-July; it was called Shemu

or Shomu.

The ancient Egyptians believed the Nile’s springs to

have origi- nated in paradise — or at the first

cataract, near Abu (Elephantine). The water of the Nile

was considered to have nutritive value; it not only served

as a symbol of purity and renewal but

it visibly gave life to Egypt

every year, bringing forth abundance. The river was also thought to

contain healing properties, and it was frequently used in medicinal

pre- scriptions.

The people of Ancient egypt dedicated many songs to the Nile, such as the “Hymn to the Nile,” “Adoration of the Nile” and “Hymn to Hapi.” Hapi was

the androgynous god of the Nile, also known as “Son of the Nile” — and yet, Hapi was not considered to be responsible for the

annual inundation. This honor and grave responsibility went to Khnemu, the ram-headed god who

was worshipped as

the “God

of Floods.” Khnemu was credited with “bringing forth the waters” from the first cataract, where he was believed to dwell.

The people

of Egypt tradi- tionally expressed profound gratitude to the Nile and its deity for the abundance

of crops that provided sufficient food for the coming year. Kings and

chaos

Ancient egypt emerged from the pre-Dynastic Age

in 3100 BC and its civilization of dynasties endured for over three millennia. The enor- mous task of categorizing

Egypt’s history was first taken up during the third century BC, by an Egyptian scholar and priest named Manetho,

from Tjebneter (Sebennytos). At the request of Kings

Ptolemy I and II, he developed a chronological

list of past pharaohs and their reigns.

Manetho divided Egyptian history into 30 dynasties

(successions of related rulers, each of which ended when a pharaoh

died without

an heir or when outsiders managed to break the sequence). This classifica-

tion has been maintained throughout the ages by historians who, in

turn, have partitioned Manetho’s list of kings into three time-periods

known as Kingdoms and three more periods of internal

political unrest

known as Intermediate Periods.

It

is important to bear in mind that dates often vary by several hundred

years, depending on

the historical

source

one consults, and in

some cases dates may overlap as a result of the royal tradition of co-

regency.

It is generally accepted that

the 1st Dynasty began with the unifi- cation of the two lands by King Narmer in 3100 BC, establishing

him as the first pharaoh. As king of Upper Egypt, Narmer conquered Lower

Egypt, thus uniting the two lands under one ruler for the

first time in history. (A

competing version

holds that this honor went to King Scor-

pion

or King Menes — or that they were one and the same person.) As a unified

entity,

Egypt would stand to benefit and

prosper

from coop- eration rather than competition.

It is at this time that hieroglyphic writing made its first appear-

ance. As

the people

amalgamated, improved communication was

needed to ensure a prosperous harvest for the growing population and the successful administration and development of the country.

The capital

of the newly-unified Egypt was founded at Mennefer (Memphis),

meaning “Established and Beautiful.” This site

was selected because of its strategic position at

the apex of the Delta, between Up-

per and Lower Egypt. Mennefer was also known as

Ineb-Hedj (“White

Wall,” a reference to the white wall enclosing the town’s most promi- nent

landmark, the royal palace). Mennefer, or Ineb-Hedj, was the offi-

cial capital during the

3rd Dynasty and remained an important

religious and administrative center throughout

ancient Egyptian

history. It was here that the pyramids and

royal necropolis of Giza and Saqqara were situated.

Egypt flourished

during the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and

New Kingdom. These empires were separated by periods of strife and

decline known as the

1st, 2nd and 3rd Intermediate Periods,

when Egypt lacked a strong central government and was racked by internal

political

turmoil. Foreign trade and contacts with other lands also

at- tracted covetous attention from abroad, resulting

in

foreign invasion.

The 1st and 2nd Dynasties comprise the Early

Dynastic, Archaic or

Thinite Period.

The Old Kingdom began

during the 3rd Dynasty, c. 2700 BC. This period

is known as

the Era of Stability, or

the Pyramid

Age.

For 500 years, Egypt experienced tranquility and prosperity, particularly during the

4th Dynasty, where grand achievements were attained in art and

architecture in the form of the construction of the pyramids. During this

time, an efficient administrative

system was established as the gov- ernment became more centralized.

However, a breakdown within the

central administration arose as a result of the dispersion of duties and powers.

This decline brought about the collapse

of

the highly- structured

society

of the Old Kingdom.

The 7th Dynasty gave rise to the 1st Intermediate Period (c. 2150

BC). This

was a time of internal conflict, revolution, riots,

strikes and civil war that

lasted

until

the

10th Dynasty. Eventually,

order and pros- perity were restored; battles were fought and won, resulting in the re- unification of the land and paving the way to the 11th Dynasty (c. 2050

BC), inaugurating the

Middle Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom is also known as the Period of Greatness and Rebirth. The finest

Egyptian literature and craftsmanship in jew- elry

and art date back to this period, never to be surpassed. The

Middle Kingdom was prosperous, as the administration was reformed and new

cities (or niwty)

were founded. The Egyptians expanded into Nubia and increased their political power, foreign trade

and economic strength. A

new social class (a middle class) emerged during this period and gained influence, as it comprised a new population that was willing and pre-

pared to work hard for the growth and expansion of the nation.

During the Middle Kingdom, Uast or Waset (Thebes,

present-day Luxor

and Karnak) first gained prominence.

Uast (“Dominion”)

became the nation’s capital during the 12th Dynasty. Uast was home to the most significant and wealthiest religious centers until the Late Period; it reached its pinnacle

as the capital of Egypt during the New Kingdom, particularly during the 18th Dynasty when it served as the religious

heart of Egypt. However, external forces

(primarily from the east) re-

sulted in the fragmentation

of the state, bringing down the era of the

Middle Kingdom.

The 2nd Intermediate Period began with the collapse of the Mid-

dle

Kingdom during the 13th Dynasty (c.

1775

BC). These turbulent times lasted over two centuries; disorganization and brief reigns by weak

foreign rulers were typical. During the 14th Dynasty, the Asiatic Hyksos, known

as “Foreign Kings”

or “Shepherd Kings,” took over

as rulers of Egypt. The Hyksos, who traveled

across the desert and settled

near the eastern border of Egypt,

established trading centers through-

out the Delta, expanding control over most of this region. Their origins are

unclear, but most scholars agree that the Hyksos likely came from Palestine or Syria. These “vile Asiatics,” as the Egyptians called them, had frizzy hair and curly beards as illustrated in pictures from

this

era. The new capital was established at Per-Ramessu (“House of Ramses”),

otherwise known as

the

town of Avaris.

When King Ahmose finally expelled the Hyksos, thus

re-unifying Egypt, the New Kingdom

was ushered in. The New

Kingdom began with the 18th Dynasty (c.

1550 BC); this era is also known as the Great- est Era and Golden Age. During this time, the population has been esti- mated

at close to 3 million, quite a high figure for the times.

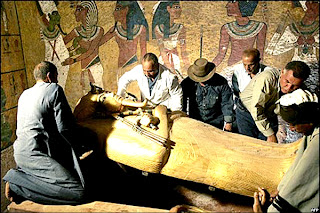

It was during the New Kingdom that the most remarkable figures

ruled the land of Egypt.

Pharaohs such as Tuthmose I to IV, Hatshep-

sut,

Amenhotep I to III, Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV), Tutankhamen,

and Seti I and II reigned during this prosperous time. The Ramessid Era also

occurred during the New

Kingdom, during the reigns of Ramses I

through XI. During the New Kingdom, Egypt reached

new heights of power

and greatness. The worship of Amen, “the Creator,” was restored and the capital was relocated to Uast.

However,

during the highly controversial

reign of Akhenaten, the

capital was moved to Akhetaten

(Amarna). Political and religious dif- ferences between the priesthood,

the

military and government officials,

along with increasing foreign pressure from

the

Hyksos and Kushites (Nubians), brought on the decentralization of

the

state and served as catalysts to bring this era to

a close. The 3rd Intermediate Period began

with the 21st Dynasty

(c.

1087 BC). At this time, the Egyptian empire crumbled and was overtaken by the Kushites,

and later, by

the mighty Assyrians.

The Late Period began with the 25th Dynasty (c. 712 BC), when Egypt was under Kushite power — and twice, later,

under Persian rule.

This was a troubled era. In 332 BC, the Greeks came to power and

es-

tablished the 31st Dynasty, ushered in by

Alexander the Great and con- tinuing as the Ptolemaic Dynasty. The

capital was moved to a settle- ment called Raqote, which was re-named Alexandria by the

Greeks in

honor of the founder

of the dynasty

and the city.

The empire, however, crumbled under the formidable weight of

the Roman invasion in 30 BC,

which brought the end of ancient Egyp- tian

civilization, culture and history.

Egypt became a province of Rome. Pharaohs no

longer ruled their land.